In this section, clicking on an image will usually enlarge it

For additional analysis based on responses to this web page visit “UK Zero Carbon Ship”

Can Commercial Shipping achieve net zero carbon by 2050?

The basic assumption of this study is that IPCC are correct in their assesment of the impacts of Climate Change and what needs to be done to mitigate its effects. (Note, however, that in my review of climate science under the Environment tab, I question the reporting of science by IPCC. Fortunately we may have more time to wind down our dependence on fossil fuels. As we shall see, that is just as well, as net zero by 2050 is improbable)

There are less than 30 years between now and 2050 when IPCC are seeking a zero carbon world. 30 years is (roughly) the life cycle of a ship. If we are going to achieve a useful result, then we need to start acting NOW. What, if anything, can the shipping community contribute to that target?

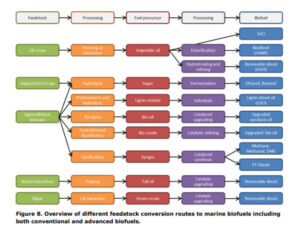

In summary, the development aims for ships that have applied during the last decade need to be refocused. The only way the shipping industry can approach zero carbon operations is by switching to hydrogen, or hydrogen derivative, fuels. Development focus over the last decade that has led to lower pollution from ships (for example, the LNG powered P&O cruise ship Iona) simply does not generate sufficient reduction in CO2 to impact on climate change

On the one hand, I am encouraged that the technologies exist to transform the shipping industry into something close to zero carbon operation (though some aspects need to be scaled up to industrial use). On the other hand I doubt the political will to make it happen in the timescale required.

One problem is that hydrogen is difficult to store safely, and even derivatives such as ammonia require pressurised and/or cooled storage, and a greater volume per unit of energy too. This will make it difficult to convert existing ships to the new fuels. Success at scale may have to rely on fleet replacement.

There is a circular problem. Shipowners will need confidence that there will be sufficient supply of appropriate hydrogen based fuels distributed to where ships need to load bunker before they will commit to building new ships, or converting existing vessels. On the other hand, governments and/or investors will be reluctant to construct new renewable hydrogen generating plants (from which safe hydrogen derivative fuels can be made) until they are assured that there will be sufficient ships passing their coasts and requiring bunker; and/or suitable tankers exist to transport the hydrogen derivative to where it is needed. An additional frustration about this loop is that the generation of renewable hydrogen could generate much needed revenue for countries most affected by climate change because of the availability of plentiful and reliable solar power or wind.

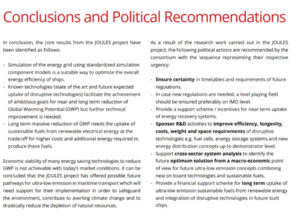

The International Maritime Organisation (a UN Body) has proved to be far too slow to achieve results. The shipping industry itself has demonstrated that it will adopt new technologies, but only when they are proven to work. The essential Hydrogen based energy will be more expensive than classic fossil based fuels. It will probably take a mixture of seed grants, research grants, taxation, regulation and penalties to make the industry move at the pace required. Above all, an effective carbon tax will be required designed to make sure that shipowners that adopt the new hydrogen based technologies are not placed at a competetive disadvantage to the remaining traditional shipping stock. In an international environment, this will be difficult to achieve.

I cannot claim this is a scientifically rigorous exercise. None of the data is mine. I have tried to acknowledge sources, and if I have failed to do so anywhere, I sincerely apologise, I am simply an observer trying to make sense of a complex subject.

I started by wondering whether the shipping industry might be able to make a constribution to a zero carbon world. My journey had many surprises, and I can only describe what I have found out.

It goes something like this

Until about 2018 the shipping industry was focused on reducing pollution. Luckily this work would also lead to significant potential reductions in GreenHouse Gas emmissions( GHG), but not enough

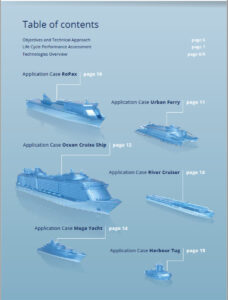

A lot of work was done and it was realised that significant GHG reductions were possible. I have used the JOULES project (An EU research programme running from about 2016) to indicate how the industry was thinking. This project took a number of “application cases” that demonstrated that, from a 2018 starting point, certain progress could be achieved by 2025. Much more, with new technologies, might be achieved by 2050

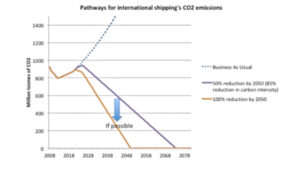

But the reality is that, even if the projects proposed in the Joules Project had been implemented, the scale of the problem is so large that there was no chance that the proposed gains could have been achieved to a meaningful extent by 2025 across the world fleet.

Looking further ahead to 2050, some new technologies were proposed

But the intervention of IPCC changed the rules, lifted the bar. Instead of pollution, the goal had been shifted to Climate Change. The rumours grew, but eventually in 2021, IPCC declared that the goal had to be close to zero carbon dioxide emissions by 2050,

This left the shipping industry (and the legislators) on the back foot.

According to the 3rd IMO GHG study. shipping was responsible for about 2.5% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (probably an underestimate). That does not sound a lot, but it is a clearly measurable contribution to the climate change problem

Projects like the Joules report clearly established a direction of travel, but the new requirements showed that improvements in hand at 2021 were simply not enough.

Shipping (and aviation) had been left out of the progressive international agreements, such as the Paris Agreement, because they were too difficult to regulate.

In my opinion, the European Union has set up and funded useful research projects that have investigated what might be done, even if, until 2018 they were focussed on, pollution reduction rather than climate change targets.

There has been a growing appreciation that in order to achieve a zero carbon shipping world, there needs to be a migration towards hydrogen and hydrogen derivative fuels. One of the strongest candidates for this is ammonia. No progress in this direction can be made unless and until this technology shift reaches wide acceptance. It seems to be the only pathway that could be achieved widely by 2050 because it relies broadly on existing technologies.

One of the few companies that has engaged this paradigm is Ricardo PLC in the UK who have demonstrated that there are strong economic drivers toward the production of hydrogen derivatives such as ammonia in places like South America and Morocco by utilising the potential availability of hydrogen produced by renewable solar processes.

Other processes such as the pyrolysis process may make it possible to produce ammonia without having carbon dioxide as an unfortunate “waste” product. Such technologies are important, if not critical to the attempts to tame energy without adverse side effects.Various medium scale demonstrators of this process are already under way.

While it is tempting to think that in a world without oil (!) we will not need tankers, the reality is that we will still need some oil as feedstock to important chemical processes, and tankers for transporting hydrogen based fuels to where they are needed.

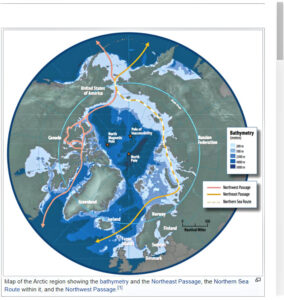

There may be opportunities to reduce the miles steamed by cargo ships. There are signs that the covid19 pandemic has forced some questioning of the desirability of very long just in time supply lines. That could lead to some manufacturing being relocated nearer to markets. Also, climate change has yielded a major benefit to shipping by opening the sea routes through the Arctic, shortening the sea journey from the far east to western Europe by about 40%.

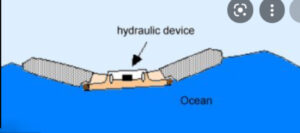

There may also be limited opportunities to reduce the requirement for energy from fuels by using wind power on some ships. However, trials in the 1980s demonstrated that such gains are route sensitive, and there are operational issues, especially the need to avoid impeding cargo handling operations, and air draught in estuaries and rivers.

So, in a sentence, I am optimistic about the technology and pessimistic about the delivery timescale.

Graham Rabbitts

August 2021

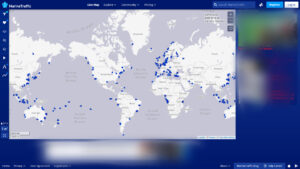

#1.1 Ships at Sea – source: MarineTraffic.com

Even before the report of IPCC Working Group 1 (WG1) had been published in August 2021, there were mutterings of concern, verging on alarm at the pace at which Climate Change was becoming evident, with flood, fire and drought proceeding to extremes on all continents’

#1.2 IPCC WG1 Report cover

It was clear that even lower targets would be set for Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions than had been current beforehand. I began to think about the impact on shipping. I soon discovered that shipping was responsible for about 2.5% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions according to the 3rd IMO GHG study. Later, I came to the conclusion that this was probably an underestimate.

My original plan was to start a discussion in the Southampton Climate Conversations group on Facebook, but it quickly became clear that the problem was too nuanced for that to work, so I decided to publish this exercise as a section of my website.

When the WG1 report hit the media it became clear that at long last people are recognising that Climate Change is happening.

Recently there has been a focus on the Green House Gas (GHG) contribution from shipping, particularly in the Southampton area.

So I thought I would try to scale the problem. The first stop was to look at the extent of shipping. I chose to use the public database from Marine Traffic

The first image (#1.1) is shocking. Nearly all these ships are burning diesel fuel and emitting CO2. Recently there has been a ban on the worst kind of bunker fuel which has a very high sulphur content (though some think that there are so many exemptions that the ban will be ineffective). References to shipping in the Paris agreement discussions were ineffective because it was too difficult to deal with. Clearly we have a problem!

But hand wringing will not do. We need to understand the problem

A good background is the Wikipedia entry on the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

“If everybody does a little, we will achieve a little. The issues raised by Climate change are on a country sized scale. Only country sized solutions will have a significant effect” That is only a slight paraphrase of the wise words of the late David Mackay.(For more on David Mackay, visit Environment on my website and select “Climate Change“)

While many broad principles had been set out at the Rio conference in 1992, progress on reaching international agreement on actions was painfully slow. By 1997 in Kyoto, a baseline was established with commitments to reduce production of greenhouse gases. It was a major achievement but it had some flaws. For example, claims by the UK government that emissions have been reduced in line with commitments ignore the fact that globalisation has meant that emissions from many UK industries (for example steel) have been exported to emerging nations. No meaningful carbon tax has yet emerged. Worse, the Kyoto ratification process is so complex that the protocol did not formally come into effect till 2005.

Fundamentally, Kyoto did not include much reference to international industries such as aviation or shipping. However, the International Maritime Organisation, which is an arm of the United Nations, was asked to consider the issues. The problem with IMO is that voting is related to the ship tonnage registered in each country. Some decisions have to be unanimous. That means that flag of convenience countries such as Liberia and Panama massively outvote traditional maritime nations. Progress happens at a snails pace. For example it has probably taken 25 years to achieve a ban on polluting heavy fuel oil used in some ships, and that agreement is very porous due to numerous exceptions. It took nearly as long to agree standards for connecting ships to shore power, a practice much demanded by environmentalists and which is beginning to happen in the UK (e.g at the new Southampton Cruise terminal).

So Kyoto was a limited success, but it was clear more was needed. December 2015 saw the Paris climate conference at which specific targets were offered by individual states. Mechanisms were also set up to assist developing countries to proceed directly to a low carbon economy. Fortunately the withdrawal of the USA from the Paris agreement was temporary and corrected when Donald Trump was not re-elected. But the fact remains that, especially in USA, there is a strong and powerful lobby group of climate change deniers.

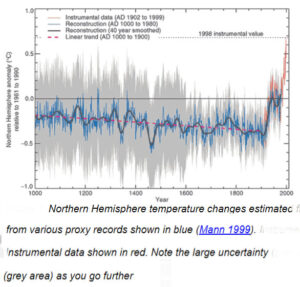

There are also those that agree that Climate is changing, but question the conclusion that the cause is human generated CO2. My oldest son is in this group. He points out that water vapour is in some ways a more powerful greenhouse gas, and leans towards the view expressed by some serious scientists (and some charlatans) that solar variation is the principle cause. My own view is that these two factors are not mutually exclusive, but you are unlikely to get research funding unless you subscribe to the human CO2 explanation. I am content to rely on the bulk of scientific thinking, but I think that it would be wise to allow some people to explore other possibilities provided their results are peer reviewed. But even within this divided world, all agree that the things that cause pollution are bad, and addressing pollution issues responds well to either view of the causes of climate change.

In 2019, it was common to see media and political assertions along these lines

“More frequent climate related crises since 2015 including massive forest fires in Australia, parts of Europe, and West Coast USA, more frequent hurricanes in the Atlantic, floods and drought on several continents, have raised awareness that climate change is not a distant threat but a current reality. The mood is right for change. “Tipping points” where climate change could race away uncontrollably are closer than we care to think about too much.”

However. I did some further research and concluded that the media and political establishment were not correctly reporting what the science actually says. This is reviewed in detail in my essay suggesting that the climate change objectives need to be reviewed. Click here for detail.

.

.

.

#7.1 Harmony of the Seas in Southampton

Reducing fuel burn in port is a minor area for GHG savings from shipping compared to the savings potentially available for ships at sea. But the emissions and noise produced by diesel generators has become a major issue with communities living near ports, including Southampton.

Two years ago there was a vigorous campaign to persuade the port management in Southampton to provide shore power to visiting ships to reduce pollution in the town and surrounding area. It was debated in several forums including a facebook page called “Southampton Climate Conversations”. I tried to point out the practical difficulties and at least one former port engineer argued that it was virtually impossible to do, and would never happen.

Shore power has been available to cruise ships in Miami USA and, I believe San Diego on the Pacific . However it has taken IMO a long time to establish suitable international standards. Issues include the wide variety of ship sizes and types; the fact that ships tend to use 110v 60hz electricity compared to the 240v 50hz supply common in Europe. Providing shore power is not like plugging in a toaster!

#7.2 Multiple cruise ships in Southampton (photo ABP)

Modern cruise ships are the size of a small town, so availability of supply becomes an issue, especially when, as in Southampton there can be as many as 5 or 6 large cruise ships in port at the same time. As it happens, Hampshire, the area surrounding Southampton, is a net energy importer, especially since the closure of the Marchwood and Fawley power stations. Furthermore, the commissioning of two new aircraft carriers based in Portsmouth has added greatly to the demand. Indeed, those 2 ships made it necessary to add a new connection to the National Grid. Supply has been slightly increased as a new interconnector from France enters the country at Lee on Solent.

Despite all these obstacles ABP is now providing shore connection at the new cruise terminal opened recently. It is far from clear how quickly they will be able to provide supply to the whole dock complex (including the other three cruise terminals, the container port, and numerous general berths). Shore Power should also be provided at the Hamble and Fawley tanker berths, and the the commercial berths in Portsmouth where cruise activity appears to be expanding.

In conclusion regarding general emissions from ships, it seems that while demand for shipping might be constrained, there will continue to be a significant requirement for cargo to be moved. There appears to be no form of propulsion that would result in zero GHG emissions. However, of the options examined, it would appear that the use of ammonia as a proxy for hydrogen offers the best possibility, within the time window available for reducing emissions to the level where any residual GHG emissions could be compensated by an effective carbon trading market.

The conclusion is dependent on 4 assumptions

Current trials of the pyrolysis process (or a successful alternative) for delivering zero GHG emissions ammonia at scale are successful

Procedures to manage the combustion of ammonia in a wide range of large diesel engines can be developed that allow a sufficiently high replacement of fuel by ammonia without unacceptable level of NOx pollution

Development of a clear carbon tax and an effective international carbon trading market which will be required to ‘mop up’ the residual GHG emissions. Given this, there should be enough commercial pressures to provide the motivation for adaptation to the new requirements.

Retrofitting the main propulsion machinery of commercial ships within the available time window is impractical..

The result could be accelerated or improved by

Systems such as the SGS wingsail that reduce the fuel burn (accepting that this is route dependent)

Development of improved antifouling systems that are non-polluting.

Provision of shore power for ships in port.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.